Programming Suicide

30 Nov 2017Software Engineers and the Ethical Obligation

A software engineer is not a tool. A tool merely assists the will of its wielder, taking no responsibility for the actions it takes. Many might hide behind the idea that a software engineer only needs to care about the quality of their work and the honesty with which they deal with employers and clients. That is the behavior of a good tool, not a good person, and a professional needs to be first and foremost, an ethical person.

Ethics does not exist in code. The purity of ones and zeros leaves little room for philosophy. Just like a star being born in the blackness of space, the laws of physic are not inherently good or bad. They only follow a logical course to an inevitable end. Ones and zeros, as well as protons and electrons, can only follow rules. Animals can only follow the course of instinct and learned responses. Arguably, humankind is limited to this as well, but if we are not, we are unique in this universe only in that we have the ability to choose how we view the world. We can see outside of instinct and build our own rules for how we act and respond to the world around us. We have learned how to value outside of ourselves, outside of our families, outside of our species, even to the point of valuing thoughts and abstract concepts more than life. In our cleverness we have gained the ability judge the value of universe and based on that, we act not as a cog within it, but as an architect. Some would call ethics a set of personal rules or laws, but those words are insufficient and make slaves of us all. Ethics are an individuals judgements regarding the value of everything. We each choose our ethics. Even when we adopt them from another person it is a choice to cling to them. In this way, we are responsible, and only in this way are we anything more than a collection of ones and zeros.

To expect a software engineer to turn a blind eye to their personal ethics in a professional setting is abhorrent. To ask anyone to think only of the will of their employer is to ask someone to be less than a human, only a tool to use and throw away. One of the biggest problems in most professions is when those pushed to the top are those who only care about blindly pursuing professional goals and being the best at what they do. The world needs professionals who develop their professional ethics in tandem with their personal ethics.

Suicidal Cars and the Trolley Problem

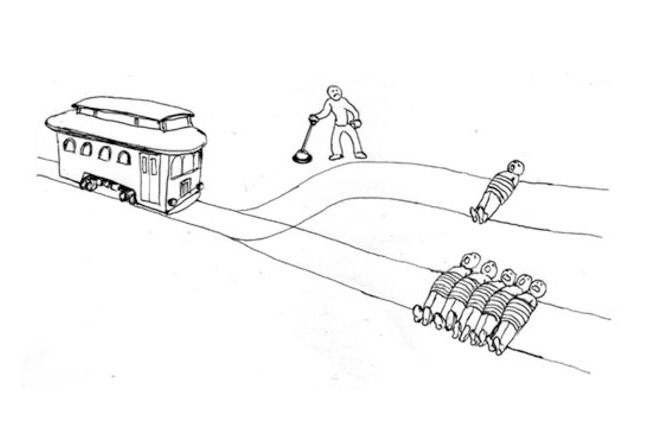

A significant a modern challenge software engineers face right now pertains to driverless cars. It is a classic ethical dilemma, but until now it’s only been an interesting situation for philosophers to think on. The classic dilemma puts the you in a position next to a railroad. An out of control trolley is headed towards a group of five people, but by pulling a lever, the trolley will be diverted down a track with only one person on it. Pulling the lever will put the single person’s death squarely on your shoulders, but also perhaps not pulling the lever you are also complicit, though to a more minor degree, with the deaths of the five other people. What should you do? Variations of this write it so that by pulling the lever you save 5 people but you will die instead. These questions didn’t have a right or wrong answer, but were more to make the reader think about their values and priorities regarding human life. It is important to remember, that these questions did not have a correct answer. Which is very unfortunate because now more than ever, we need the correct answer since this situation is more or less exactly what we have to program into a driverless car.

A significant a modern challenge software engineers face right now pertains to driverless cars. It is a classic ethical dilemma, but until now it’s only been an interesting situation for philosophers to think on. The classic dilemma puts the you in a position next to a railroad. An out of control trolley is headed towards a group of five people, but by pulling a lever, the trolley will be diverted down a track with only one person on it. Pulling the lever will put the single person’s death squarely on your shoulders, but also perhaps not pulling the lever you are also complicit, though to a more minor degree, with the deaths of the five other people. What should you do? Variations of this write it so that by pulling the lever you save 5 people but you will die instead. These questions didn’t have a right or wrong answer, but were more to make the reader think about their values and priorities regarding human life. It is important to remember, that these questions did not have a correct answer. Which is very unfortunate because now more than ever, we need the correct answer since this situation is more or less exactly what we have to program into a driverless car.

Cars will get into accidents whether or not a human is driving it. At some point, some car will have to make a choice that will result in someone dying. If a car suddenly detects a crowd of people ahead, clearly it must turn away, but what if the only option is to kill another person? What if there are three options, one with a crowd, one with an old man, and one with a child? What if the options are to run into a crowd or turn the car into a wall killing the driver? What if it’s a single person in the road? How does the car decide which life is the best to take? In the spur of the moment, human drivers have been in these situations, and based on a split second decision committed themselves to a specific fate. Because it happens in a split second, most people don’t actually choose. Many will freeze, unable to respond. Others will react instinctually, not comprehending the full situation and potential consequences. This all happens very quickly, and assuming the driver was not at fault for being in that situation, no judge or jury could fault a driver for not sacrificing their own life based on a split second decision they had to make. A driverless car however will probably have all or at least most of the information, and because it is necessary, a person will have to tell the car what life is worth more. To do nothing in this case would be to risk countless deaths. A decision must be made.

My (Two) Moral Answers

As I debated this situation, I found that there were only two possibilities that seemed morally plausible. Each possibility is defined by a moral value. I cannot argue which is the best answer, but I will at the end choose one and explain why that moral value enshrined by my choice is more important to me than the others.

1. Utilitarianism

An obvious answer to this question, we could approach this by minimizing the loss of life and setting a bunch of rules that a car would take into consideration. This is far from a perfect example, but let’s say that we value the driver’s life and each passenger’s life at 1.1 units. Other adult humans would be valued at 1.0 units, and children valued at 2.1 units. In any scenario where the car would have to decide on which life to take. The car would favor the occupant’s life in a situation where the loss of life would be otherwise even. If there was a child, the car would heavily favor avoiding the child unless more than two pedestrians or less than two occupants. This isn’t a perfect situation, and we’re running the morally dubious line of measuring the value of human lives, which never goes over well.

This method would, however, minimize the death toll in theory, and lead to the least damage to society. Also, once the measurements are known, would someone buy a car that would ever make a decision to kill them and their passengers (possibly their own child) in favor of saving a bunch of strangers who very well might be the ones at fault for being in the way of the car to begin with.

There is a grave danger in that once the utilitarian nature of driverless cars are known, it becomes incredibly easy to murder someone by bringing along five friends and standing in the road around a blind corner on a cliff-side. Once you know a car will always avoid a greater number of people, you could just force the car to kill its driver once you know their route home and a dangerous place to stand. It would then be incredibly hard to prosecute people for murder just because they’re standing in a stupid part of the road. Whenever you reduce human life to hard, utilitarian numbers, it becomes incredibly easy to kill people with math. Of course, as algorithms become more complex, perhaps we could find ways around abuse of the system.

Arguably, by making an unpopular, but logical choice, we are taking the greatest amount of responsibility and by saving the most people this is the most moral decision for someone who values utilitarianism.

2. Let the customer choose

The person using the car is the one who stands to lose their life and the lives of the people in their car. In a driverless car, there should be no reason why a passenger would be at fault for a situation where their lives are put in danger. Therefore, it should be up to them whether or not they would sacrifice themselves for others. When a programmer creates the algorithm that the car will follow, it is their moral obligation to ensure that the car will not be used for illegal purposes. Programming a car so that it never intentionally runs into people is a necessity. Programming a car so that it chooses who to kill to minimizes the damage done is perhaps someone’s moral ideal, but as there is no law saying a passenger must sacrifice their life to preserve a greater number of lives, we have no authority to force our moral preference on another person.

A line must be drawn between moral obligation, and moral preference. We as programmers are obligated to prevent people from breaking the law. We are also obligated to minimize harm done as far as possible. However, we cannot force another person to accept our personal moral code of sacrificing themselves for the greater good. The best we can do is allow them the option. Therefore we should allow a customer to set these limits themselves. It is a harsh business, but it is not something that can be ignored. We could create a default mode for those who refuse, or even a random chance mode, but before a car is driven, a passenger must make a choice, even if it is to submit to the default or to random chance. It’s like checking off the box saying if you’d like to be an organ donor. It’s a grisly business, and people can turn away if they wish, or even take the most selfish course, but that decision is on them.

Over minimizing human harm (utilitarianism), this choice prioritizes a person’s right to freedom of choice so far as they are allowed.

My Conclusion

To me, the answer seems to clearly be to let the customer choose. Earlier in this essay, I claimed that it was morally repugnant for an employer to override the ethical code of an employee and to use them only as a tool. This rule must be applied to all people. Everyone must be allowed to choose their own ethical path as far as they are legally allowed. People are individuals, some selfless, some selfish, some willing to sacrifice anything for the ones they love. As far as we are able, we must allow people to make this choice for themselves, and they must face the consequences of their actions. But then it is their responsibility, not ours. A professional serves the public, and we must know our limits.